Please stare. That’s the behavior Terry Welker wants to encourage when it comes to his artwork. “Mobiles allow people to stare,” muses Welker, an established architect and Fellow of the American Institute of Architects who has been creating mobile and suspended art installations for over a dozen years. “If you can pause and stare at something, it’s like a micro-escape from the world.”

Giving people an escape from reality is no easy feat for an artist whose work drifts above the bustle of daily life, particularly given society’s collective downward gaze, which is all too often focused on floors, steps, mobile devices, and tablets. To combat this, Welker designs his mobiles to be not only kinetic, but also appropriately scaled for the space and viewer.

“Scale is the real issue,” Welker says of creating suspended work for a space. “We sense things not only with our eyes but with our bodies, so it can’t be a work of art that just looks right; it also has to feel right for the space.” His mobiles, which tend to be more open and airy, often need to be scaled up to achieve a greater sense of mass.

His recently installed Fractal Rain, for example, a commission for the Dayton Metro Library in downtown Dayton, Ohio, is composed of wire, crystals, and prisms, materials that might otherwise go relatively unnoticed were it not for the scale of the piece. Incorporating nearly five miles of stainless steel wire, one-third mile of extruded acrylic prisms, and nearly 400 dichroic-coated Swarovski crystals, Fractal Rain fills the library’s atrium with the movement of driving rain, visible from the building’s multiple levels and central staircase. A project inspired by works from The Dayton Art Institute—including Monet’s Waterlilies, the “fractalized” Chimu Mummy Mask, and Dayton’s River history—the piece was designed, says Welker, to reflect the tension between order and chaos.

“There’s certainly order to the piece,” the artist says, “but it’s also an orchestration of near misses, where the various elements may actually collide gently with one another.” The viewer’s experience as he or she walks past the piece, as well as the light refracted by the crystals, lends to the sense of movement. The subject of rain also has a sort of chaotic meaning for Dayton and its residents, who still reference the great flood of 1913 and the havoc it wreaked on the city. “People here have a love/hate relationship with rain,” Welker explains. “Fractal Rain is a reminder that rain can be both beautiful and a threat.”

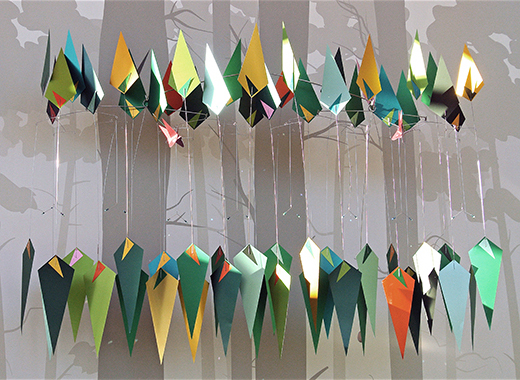

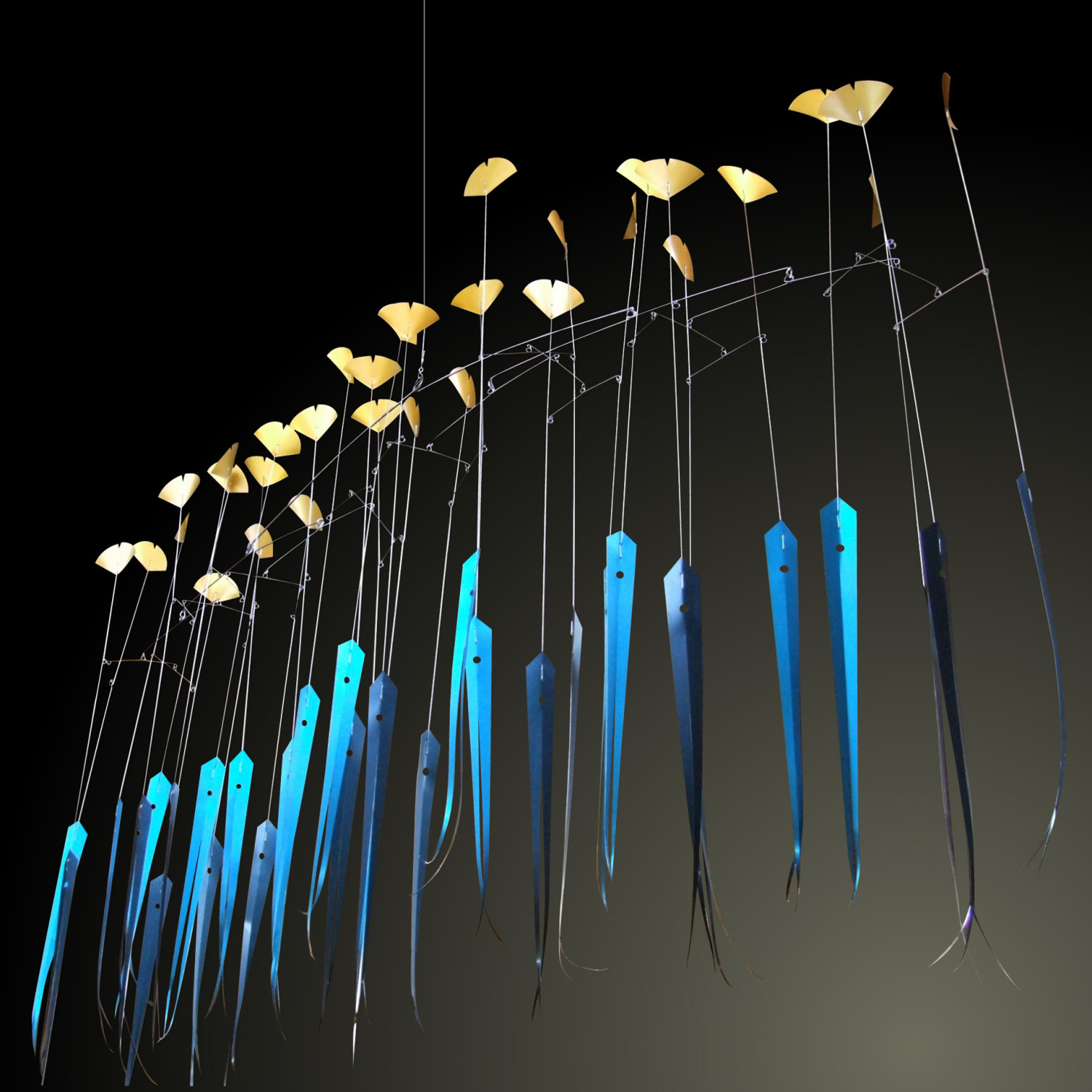

Many of Welker’s pieces likewise build on this idea of extremes: chaos and organization, positive and negative, gravity and levity, large-scale and lightweight. Like knobs on a radio, he continually adjusts color and form in the language of Alexander Calder. Just as a painter studies other painters, I reference Calder’s work to find ways to build on and expand his modern visual language. I am also very much a formalist.”

Balancing Architecture & Art

Welker carefully considers each commission with both an architect’s and a sculptor’s eye. “I look at how daylight moves through the space, how it changes during the seasons, and what kind of weather is typical for the region where the piece will be installed. I consider what will be around the space and how the piece will be viewed. What’s in front of it? What’s behind it? How much visual context surrounds it?” For spaces with cluttered, boring, or nice but visually passive ceilings, Welker looks for artful solutions that allow the viewer’s eye to “land on something better.”

Such architectural scrutiny not only helps Welker read a space for scale, light, and visual noise, but also consider how his work will interface with fire protection systems, what the structural ramifications might be, and when to hire a structural engineer. “To be able to speak the language of the architects and designers I’m creating art for is helpful—and it gives them confidence in me to be responsible for budgets and other dry stuff,” he laughs.

Welker begins most of his pieces with models, eschewing drawing and sketching for the hands-on work of building. “I don’t like to linger on paper for long,” he explains. “When you’re dealing with gravity you must be true to the materials you’re using, to balance, to form.” He creates 3D renderings in SketchUp from his models, where he can size pieces up or down to find that just-right scale for a space.

Many of his pieces are progressions of natural elements—blades of grass, birds, or his particularly iconic ginkgo leaf—each a slight variation on the one before. When paired with negative space, such progressive elements help the piece create a visual pattern. To that end, Welker pays close attention to the many joints that lend his work movement. “The joints and connections are really a part of the art,” says Welker. “The size of the various loops and hooks can affect the way the piece moves, and how the various elements touch—or do not touch—one another.”

Collaboration with fabricators is important to getting the mechanics of his artwork just right. “I’m really interested in finding people that make and do things I don’t know how to do,” he says. “With Fractal Rain, for example, I visited a wire factory in Illinois to learn all about this specific full hardness spring steel wire as I needed the wire to behave a certain way in the piece. And I found an electro polisher in Wisconsin that electro charged the steel in an acid bath to get the impurities out of it to achieve the finish I wanted. The back-and-forth of collaboration is the fun part. It’s like a team sport, and being open to these processes really allows me to do so much more in my work.”

The ultimate collaboration, however, is that with a given project’s stakeholders. “The work ultimately has to be meaningful to the community,” Welker explains. The goal, he says, is to create a sense of place. “My inspiration really comes from nature, and I want to inspire viewers to experience their own memories of nature. Part of placemaking, I think, is enabling memories. If someone sees my work and it reminds them of something, that’s the memory trigger I’m going for. I want to build on that positive emotional response to create a sense of place.”