Talk with mosaic artist Jonathan Brown, and you get the distinct impression that his work is, for him, a form of play. He’s become a master of his craft in the nearly twenty-six years since founding his company, Modern Mosaics, at the remarkably young age of nineteen. But even with dozens of projects and commissions for mosaic installations, lighting, furniture and fountains for private residences, restaurants, hospitals, stadiums, churches, and public spaces nationwide, Brown maintains a childlike wonder for breaking things apart and reassembling them into something new and beautiful.

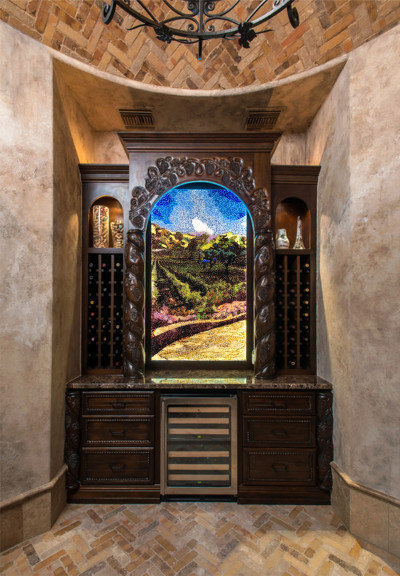

Houston, Texas US 2007

“Honestly, my first love was the sound of shattering glass,” Brown laughs. “It reminded me of the sound that pool balls make when a player breaks that first shot—that cracking sound when the balls split apart.” A drawer and maker from a young age, Brown also cites the video game Tetris as an early source of inspiration for his career.

“Tetris is really a mosaic,” Brown explains. “When I make a mosaic, just as in Tetris, I’m grabbing these colored pieces from the pile. I just fell in love with the process of sitting down with these random, broken shapes and piecing them together, and then stepping back to see this detailed image that had formed.” A backpacking trip in Central America, where he discovered Mayan mosaic art, also played a major role in his development as a mosaicist. “I didn’t even know the word ‘mosaic’ or what it was at the time,” Brown recalls of his experience. “I just knew it inspired me.” He returned to Houston uncertain of what he was doing, only that he wanted to make pieces like those he’d seen in Central America.

His first works were made from “boxes of broken stuff,” ceramic tile, and glass on any flat surface he could find. An experiment cutting one-inch glass squares resulted in very tiny pieces, which Brown discovered were perfect for mosaic lighting. He soon discovered that he could purchase sheets of colored glass to create larger mosaic pieces and that was it: he was off and running.

Going Beyond Glass

Today, Brown works in a 7,000-square-foot studio, the entire fourth floor of a long, tile-roofed building in Midtown Houston. Crates of colored glass and rows of glass sheets line the walls and floors. He employs three studio artists who not only help Brown execute his designs, but also create their own original pieces. In addition, he often uses several additional craftspersons for very large projects. He spends a good deal of time working with staff, sharing tricks and tips with them as they work, encouraging them to experiment and play with their craft to keep the studio’s collective enthusiasm and individual creative juices flowing.

Madison, WI US 2016

Though Brown continues to make smaller mosaic pieces, which he sells through his website, much of his time these days is spent applying for and working on large-scale commissions. His recently completed Technology in Motion in downtown Madison, Wisconsin, represents his largest project to date. Comprised of sixty 8′ x 4′ painted panels embedded with 500 LED nodes, the piece is designed to mimic the appearance of a large waterfall flowing down the exterior of the ten-story building. (The RFP and artist selection process for this project were managed by CODAworx.) Brown is now experimenting with a technique of applying a translucent mosaic over painted pieces like that of Technology in Motion, to outstanding effect.

While most of his commissions are of the more traditional glass mosaic variety, Brown seeks out opportunities to create pieces using less-common materials and techniques. A 60′ floating wall panel he created for Miami Valley Hospital in Dayton, Ohio, for example, is comprised of hand-cut strips of stained glass, encased in clear resin. The Trees of Fondren Park, a commission for Memorial Hermann Children’s Hospital in Houston, is a sort of suspended mural, with large hanging resin discs forming the canopy for five life-size trees.

Miami Valley, Ohio US 2011

Lately, Brown has even been creating mosaic from paper. Working with Japanese, Italian, and French pulp paper, he rips the material as he would glass, layering it to create a “paper painting.” The paper is then covered with a UV-resistant acrylic coating and backlit with LEDs. It’s a process born both of his curiosity and the need to create a less-expensive mosaic option for his clients. “My glass mosaic is made to last forever,” Brown muses. “I fully expect that in 400 years, people are going to be unearthing my glass mosaic pieces. But glass also comes with a price, and design firms sometimes come to me with tight budgets. The paper mosaics I’ve developed have an interesting look and are absolutely gorgeous. And they’re significantly less expensive to create than glass mosaic.”

The Old and the New

Regardless of the material, Brown begins all his pieces the old-fashioned way, with a hand-drawn sketch. Working from his client’s preferences for color and subject (if provided), he sketches from his imagination in a “futurism style,” breaking each color down in a series of gradating bits to feather shades from dark to light, one into the next.

Carlton Woods, Texas US 2014

While mosaic making still involves what Brown calls the “down and dirty” business of sand, glue, hammer, and chisel, the arrival of new technologies and materials over the last two decades has changed his craft in significant ways. His hand-drawn sketches are now scanned into Photoshop, where he can add, edit, and delete layers of color as many times as he’d like. Once the design is complete, it’s printed, laminated, and placed in the projector, casting the image onto the substrate on which the mosaic pieces will be placed. He draws the projected image onto the substrate, marking where to place specific color as a guide for his studio team to follow. (He prefers to place color freehand if he’s doing this work himself).

New kinds of glass, resin, and UV-resistant acrylic provide stronger, more durable options for mosaic making, and Brown is experimenting more with the incorporation of LED into his pieces. His work is constructed in panels that are then shipped to the installation site, where he “stitches” the panels together to give the appearance of a single, seamless work of art.

The thing that has remained consistent in Brown’s work over these years is the reaction viewers have to it. “I see the same expression on the faces of people who are viewing my work,” he explains. “It’s like they can’t figure out how in the world such detail can be achieved with such tiny little chips of glass. People say they see all sorts of random images in my work, like faces or objects. It’s a unique experience for every viewer; everyone sees what they know. That’s the way the world runs.”

View Artist Profile

Contact Jonathan Brown